Around 120,000 years ago, the practice of burying the dead emerged among early Homo sapiens and their Neanderthal counterparts in the Levant region of western Asia. This synchronicity in burial customs raises intriguing questions about potential cultural interactions and shared beliefs regarding death and the afterlife. Recent research by teams from Tel Aviv University and the University of Haifa sheds light on this ancient practice, offering a nuanced understanding of how these two closely related species engaged in the ritual of burying their deceased.

What stands out in this study is the assertion that both species, despite their differences, may have been influenced by a common socio-cultural milieu. This is pivotal, as it suggests that early human cognition concerning death and the treatment of bodies could have developed under similar environmental pressures or social conditions. The evidence points to the Levant as a potential ‘cradle’ for these funeral practices, predating burials found in both Europe (among Neanderthals) and Africa (among Homo sapiens).

As researchers dove into the burial sites, they identified a complex interplay of shared customs and competition for resources between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. They propose that the uptick in burial practices may have stemmed from intensified competition for living space and materials as the two groups coexisted in the Levant. This hypothesis not only posits a fascinating dynamic of cultural exchange but also underscores the survival instincts underpinning their social behaviors.

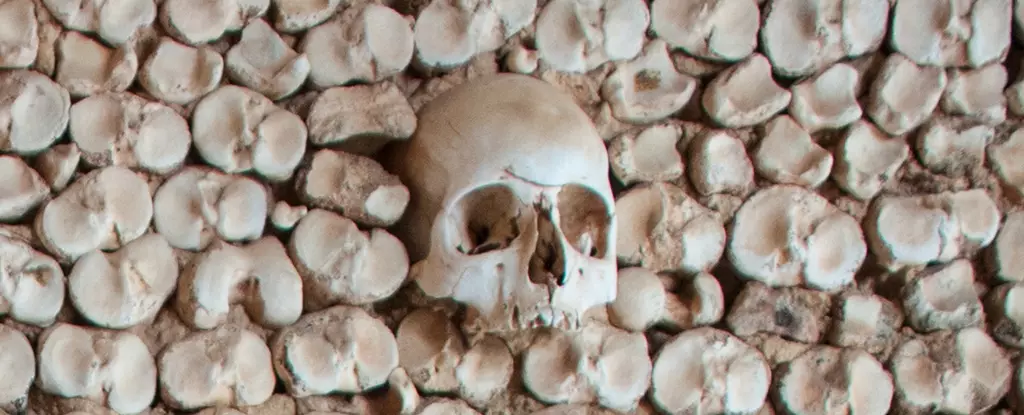

The study details 17 Neanderthal burial sites alongside 15 associated with Homo sapiens, revealing similarities in the intent behind these rituals. Both groups displayed a willingness to inter individuals of all ages, emphasizing a cultural acknowledgment of death that transcended mere survival instincts. However, notable variations cropped up in burial practices, including significant differences in grave goods and burial locations.

A key finding of this research lies in the manner and variety of burial practices between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. The Neanderthals tended to prefer deeper burials in caves, suggesting a more practical approach to interment, perhaps motivated by environmental factors such as weather and predation. In contrast, Homo sapiens favored burying their dead at cave entrances or in open rock shelters, indicative of a possible ritualistic significance tied to these locations.

The positioning of skeletons within graves also presented an intriguing contrast; Homo sapiens often arranged their burials in a fetal-like position, perhaps symbolizing rebirth or homage to the cycle of life. Neanderthal burials, on the other hand, exhibited a broader range of skeletal arrangements, hinting at perhaps varying beliefs or customs connected to death.

Furthermore, the grave goods accompanying these burials reveal cultural nuances. Both groups included items like small stones, animal bones, and horns, yet significant differences arose in the decorative choices. Neanderthals made greater use of rocks that may have served as simple gravestones, whereas Homo sapiens adorned their graves with ochre and decorative shells, clearly indicating a more complex aesthetic or spiritual understanding.

As Neanderthals vanished from the archaeological record roughly 50,000 years ago, a stark phenomenon unfolded—human burials in the Levant ceased for an extensive period. This gap raises questions regarding the cultural implications of Neanderthal extinction on Homo sapiens’ practices. The researchers suggest a resurgence of burial practices only at the advent of the Paleolithic era, coinciding with the rise of sedentary lifestyles among groups like the Natufians.

This revival may reflect broader societal changes, such as an evolved understanding of community and the imposition of new belief systems surrounding death. The implications of these findings signal a rich tapestry of meaning encoded in burial practices that requires further exploration, drawing connections to how early human societies began to shape their identities through the act of remembering the dead.

The study of early Homo sapiens and Neanderthal burial practices not only illuminates our understanding of these ancient populations but also opens doors to a larger discourse on the evolving human experience of death and memory. The interplay of competition, shared rituals, and eventual changes following the Neanderthals’ extinction provides an essential context for understanding the development of human culture in its entirety.

Leave a Reply