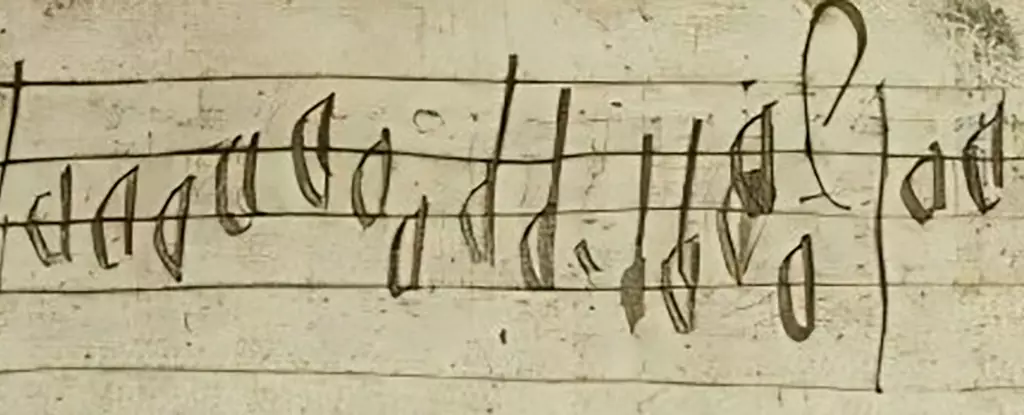

Music is often perceived as a universal language, capable of evoking memories and emotions that bridge generations and geographical divides. The recent discovery of a fragment of sheet music from 16th century Scotland shines a light on the musical landscape of a period that remains largely obscure. This 55-note snippet, residing in the margins of an important religious text—the Aberdeen Breviary—has opened new avenues for understanding Scotland’s liturgical culture prior to the Reformation.

The Aberdeen Breviary, published in 1510, is not just any old manuscript; it holds historical significance as the first complete book printed in Scotland. Yet, within its pages—specifically in its neglected margins—researchers from KU Leuven and the University of Edinburgh stumbled upon a musical notation that bears the potential to reshape our understanding of religious practices during that era. The fragment, discovered in 2011, reveals details about a musical tradition that otherwise might have faded into obscurity.

The recovered notation has been identified as a musical guide to a lesser-known Christian chant called “Cultor Dei, memento,” which translates to “Servant of God, remember.” This piece is still performed in some Anglican churches today, thus serving as a bridge between the past and the present. However, ambiguity surrounds the intent of this notation: Was it composed as a guide for instrumentalists, or was it meant for vocalists in a choir setting? Despite the uncertainty, this fragment has provided scholars with invaluable insights into the cultural fabric of pre-Reformation Scotland.

Musicologist David Coney articulated the excitement surrounding this find, stating it enables modern audiences to “hear a hymn that had lain silent for nearly five centuries.” The sheet music represents a rare glimpse into the polyphonic tradition of the time, where multiple melodies intertwine harmoniously. This discovery not only validates but challenges the long-held notion that pre-Reformation Scotland lacked a rich musical heritage.

The intrigue doesn’t stop at the music itself; the broader historical context surrounding the Aberdeen Breviary adds another layer of depth. The study of its ownership and creation ties it to significant locations such as Aberdeen Cathedral and St. Mary’s Chapel in Aberdeenshire. Interestingly, while the musical fragment enriches the religious narrative, the identity of the composer remains elusive. This raises further questions about the contributions of unrecognized figures in the realm of music who existed within the grand tapestry of Scotland’s ecclesiastical history.

James Cook, another musicologist involved in this research, emphasized that this discovery counters the prevailing belief that pre-Reformation Scotland was devoid of musical sophistication. Instead, it unveils a tradition of intricate musical composition that existed amidst the cathedrals and chapels, mirroring developments across Europe.

The significance of this fragment extends beyond its historical value; it serves as an impetus for future exploration. The researchers have expressed enthusiasm about the potential for further musical finds hidden in other sixteenth-century texts. Indeed, margins and blank pages of similar manuscripts might still conceal melodies waiting to be uncovered. As Paul Newton-Jackson suggests, the promise of additional discoveries beckons scholars to engage in a renewed examination of Scotland’s archives and libraries.

In a broader context, these glimpses into Scotland’s musical past challenge the narratives that have been accepted thus far. They encourage a re-evaluation of the cultural and artistic life during a time marked by upheaval and transformation. As researchers continue to delve into this period, the interplay between music, history, and identity in Scotland will undoubtedly reveal complexities that deepen our understanding of both sacred and secular life at that juncture.

The unearthing of a 55-note musical fragment serves not only as a reminder of Scotland’s rich but often overlooked musical tradition but also as a critical turning point in the study of pre-Reformation culture. As we reinterpret the history of music in this era, we come closer to understanding the intricate web of influences, expressions, and identities that have shaped Scotland’s cultural landscape. The melody that once lay silent now resonates, reawakening a lost past that deserves to be celebrated and explored.

Leave a Reply